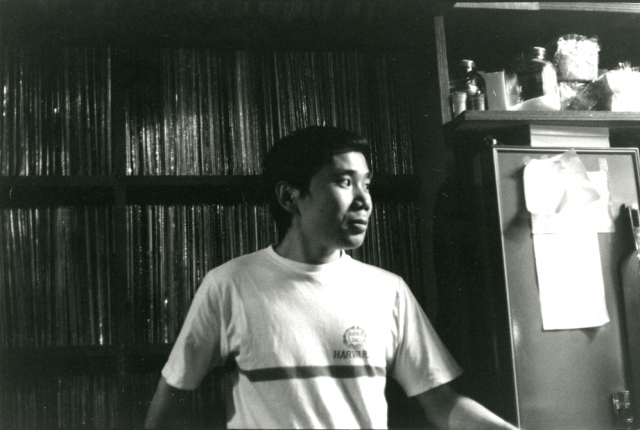

Haruki Murakami is an author who writes very un-seriously about serious topics. His books are filled with places, foods, and activities the author and thus, the protagonist loves and are often written in a dream-like manner with the most imaginative descriptions but in the end, are attached to sturdy messages surrounding the post-modern man. This essay will analyze one of such works, “Hard-Boiled Wonderland and The End of The World”. Using two vastly different settings sprinkled with unique narrative devices, the book tells the story of a post-modern man soon to lose his mind to the influences a cyberpunk Japan has imbued his consciousness with. I will attempt to analyze the Freudian and Jungian influence on the work, with Western modernism at the core, since Murakami himself is deeply influenced by the consumerism and modernity of the West.

Hard-Boiled Wonderland and The End of The World pits two worlds against one another, one real and one imaginary but by the end of the book neither remains entirely real or fictitious. The worlds can be differentiated by just the way they are written. The protagonist in both these worlds uses “I” to refer to themselves, but the one in Hard-Boiled Wonderland uses the formal pronoun “Watashi” while the other uses the informal “Boku”. However, in both these stories the protagonist is never given a name and is only referred to as “The Dreamreader” in The End of The World and as Calcutec along with other similar names in Hard-Boiled Wonderland.

The world of Watashi is a post-modern, cyberpunk version of Japan where he works for an unseen corporation called the “System”. The use of simply the word System an echo of van Wolferen’s characterization of the State. Watashi is portrayed as being smart and sure of himself but not superhuman. He is a “calcutec”, an encoder of data with the help of the implants in his conscious and subconscious mind. The date he encrypts only he can read. Opposed to the Calcutecs are Semiotecs, pirates of information who stop at nothing, using torture and mutilation to extract information. It is natural for the narrator to be uneasy in such an environment. However, as a detective-like figure in a hard-boiled setting, he is given some sort of extraordinary powers which aren’t even explained away. He is characterized by a sense of rebelliousness and marginality, while his principal talent is for dealing with unusual, especially dangerous, situations.

There is a sinister characterization of the city as a shell; beautiful on the outside in the most modern sense but teeming with evil on the inside. The System that the narrator works for is an extension of the State itself and thus is all-powerful and omniscient. Murakami deeply distrusts a controlling state, which is portrayed in several of his works. There is a sense of irony since the narrator believes himself to be a completely isolated individual but works for a postmodern, late-capitalist consumerist State. Just like in “A Wild Sheep’s Chase”, another of Murakami’s books, the State is always present but is difficult to pin down and gauge its existence. An example of the narrator being controlled is the revelation that the private gig he was given by the Scientist was a façade and it was instead an attempt to learn the results of an experiment performed on the Narrator. It is the result of this experiment s his subconsciousness to form the Town and ultimately lose his mind. The Narrator is not an individual, but rather just an extension of the State.

In the Town at The End of the World people have no minds. When newcomers enter the Town, they must strip away the ‘shadows’ that are the grounding of the self. ‘Mind’ in this work encompasses human nature’s irrational, affective, and passionate aspects. According to the Professor in The Hard-Boiled Wonderland, the mind forms an identity of self: ‘And what is identity? The cognitive system arises from the aggregate memories of an individual’s past experiences. The layman’s word for this is the mind.’

The Town is guarded by the Gatekeeper, whose house is filled with countless types of bladed weapons. He spends hours of his day sharpening every single one of them. His occupation itself is to use these weapons to guard the Town, however, the narrator is confused as to protect it from what. The Gatekeeper can thus be seen as a subconscious extension of the State/System from the City with its duty of protection and contrarily the control system in the form of shadow cutting. The Town is thus not that unlike the City, in the way that there is potential for unhinged violence.

People at The End of the World lack this ‘mind’; consequently, their world is calm and peaceful. The Colonel says, ‘You are fearful now of losing your mind, as I once feared myself. Let me say, however, that to relinquish yourself carries no shame. . . . Lay down your mind and peace will come.’ (1992: p.318) The Dreamreader comes to appreciate the Town. He describes this world without self: ‘No one hurts each other here, no one fights. . . Everyone is equal. . . . They work, but they enjoy their work. It’s work purely for the sake of work, not forced labor. . . . There are no complaints, no worries.’ (1992: p.333)

This is Murakami’s postmodern utopia, but it is realized only through the sacrifice of love and respect which have long been considered positive values. Although the Dreamreader, who still has a trace of mind, loves the librarian, his love can never be requited, because she has no mind. According to the Professor in The Hard-Boiled Wonderland, the mind forms an identity of self: ‘And what is identity? The cognitive system arising from the aggregate memories of (an) individual’s past experiences. The layman’s word for this is the mind’ (1992: 255).

There are always two sides to any question. That is the absolute root of all conflicts between men throughout history. All conflicts and wars can be traced down to a difference in opinion. Therefore, in a world driven by modernism that is increasingly dominant in the way it treats power, there is a further divide along the lines of individualization and totalization. The characters in Murakami’s work are hypermodern and thus lead completely individual lives. There is no conflict between them, but they never seem to bother each other. There is a peaceful harmony that can only exist in a utopian modernist world.

There is albeit a dark side to this, in the form of a ‘hard-boiled Japan’. The portrayal of the System/State helps Murakami as it locates an evil presence throughout the landscape of Tokyo. In this setting, evil isn’t something strange or foreign, it is instead a state of normalcy, against which the protagonist’s heroism stands out as rebellious in a wholesome manner. Interestingly, the State isn’t the only source of danger as many more kinds lurk behind the clean and urban façade of modern Tokyo. The streets crawl with Semiotecs who are ready to torture and even kill Calcutecs for information to trade as we judge from their attempts to extract information from the protagonist both themselves and through the use of other, innocent people. Then there are “INKlings”, hideous creatures who lurk underground and feed on human flesh. They live and control the entire subway as is confirmed by the protagonist with the discovery of a lone shoe belonging to a businessman in the subway.

This sinister characterization of the city as a beautiful shell, teeming with evil and danger, is definitive of the hard-boiled setting, for it underscores the notion that the evil lurking in society is not isolated psychopathy, but an endemic feature of the modern (or in this case, postmodern) social structure. In such a landscape, according to Cawelti, we find “empty modernity, corruption, and death. A gleaming and deceptive facade hides a world of exploitation and criminality in which enchantment and significance must usually be sought elsewhere” (Cawelti 1976, 141).

The juxtaposition of the city seems mild at first and makes for an engaging reading experience but as the story goes on, several philosophical questions arise. What are the real stakes of the story? Does the continuation of existence at The End of The World constitute living or does the narrator face a form of death of his consciousness? This matter is further complicated when we learn that The End of The World is in fact artificial and carefully created by The Scientist, having drawn on his experience as a filmmaker. This was done as an experiment to see what effect a third circuit would have on the brain. As the story goes on, we expect everything to be revealed by the Scientist, but we never learn what happens to the protagonist once the supposed death occurs.

Murakami’s first genuine foray into the postmodern idea of the “commodified sign,” as well as the greater ramifications of a social and economic system that converts knowledge (among other things) into a commodity to be bought, sold, or, in this instance, stolen. The emphasis in Hard-Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World on the power and value of information—particularly reified information—is not a uniquely postmodern phenomenon, but it is especially pronounced in the postmodern moment, and perhaps at no other time in history has the importance of information been so integral to everyday life.

What does the subtext present throughout the story suggest? Does Murakami encourage us to escape the state-controlled consumerist state and withdraw into our own minds? However, we see in the story that while the protagonist at The End of The World chooses to remain, the one in Hard-Boiled Wonderland had no such choice, his choice was already made by the Scientist and by extension, the State. In the end, he is succumbing to his subconscious, i.e., the power of the State through which his mechanized subconscious was created. The only two choices that remain to the narrator are precisely mirrored by the reality of the blank utopia of contemporary consumerist society: a utopia of empty consumerism, carefully managed by a System of political, industrial, and media enterprises. In ontological terms, it can be argued that the protagonist’s entrapment in his subconscious is a form of death, and his decision to remain, and thus to capitulate to State power is a form of suicide. Surely the end of the novel suggests neither the reaffirmation of life over death nor of clarity and truth over mystery and doubt. Rather it simply reinforces our understanding (or at any rate Murakami’s understanding) of reality: that the postmodern State is impregnable, irresistible, and that we ourselves participate in our own corruption by it.

Leave a comment